A Successful Visualization of the Idea of Tokyo

In October 2023, Hibiya was hot like summer, and the city teemed with foreign tourists. Tokyo International Film Festival opened with Perfect Days, which was on everyone’s lips due to Koji Yakusho winning Best Actor at the Cannes Film Festival. Once I sat in my seat and the movie theater became dark, I watched Hirayama, played by Koji Yakusho, waking up in a small, old apartment room. I was drawn into it the second he awoke in his wooden six-tatami mat room. The film is set in Japan and is in Japanese, but there’s no doubt it’s Wenders’ film. I knew it would be an essential work even before the end credits played, especially for creators that go back and forth between Japan and abroad. No other film had succeeded in translating the image of Tokyo in the 2020s into a visual language. This visualization of the city will become a common language for those who live in Japan and those from abroad to communicate with. We’ll be able to say, “That Tokyo.” The new year has rolled in, and several months have passed, yet the reverberations of Perfect Days remain.

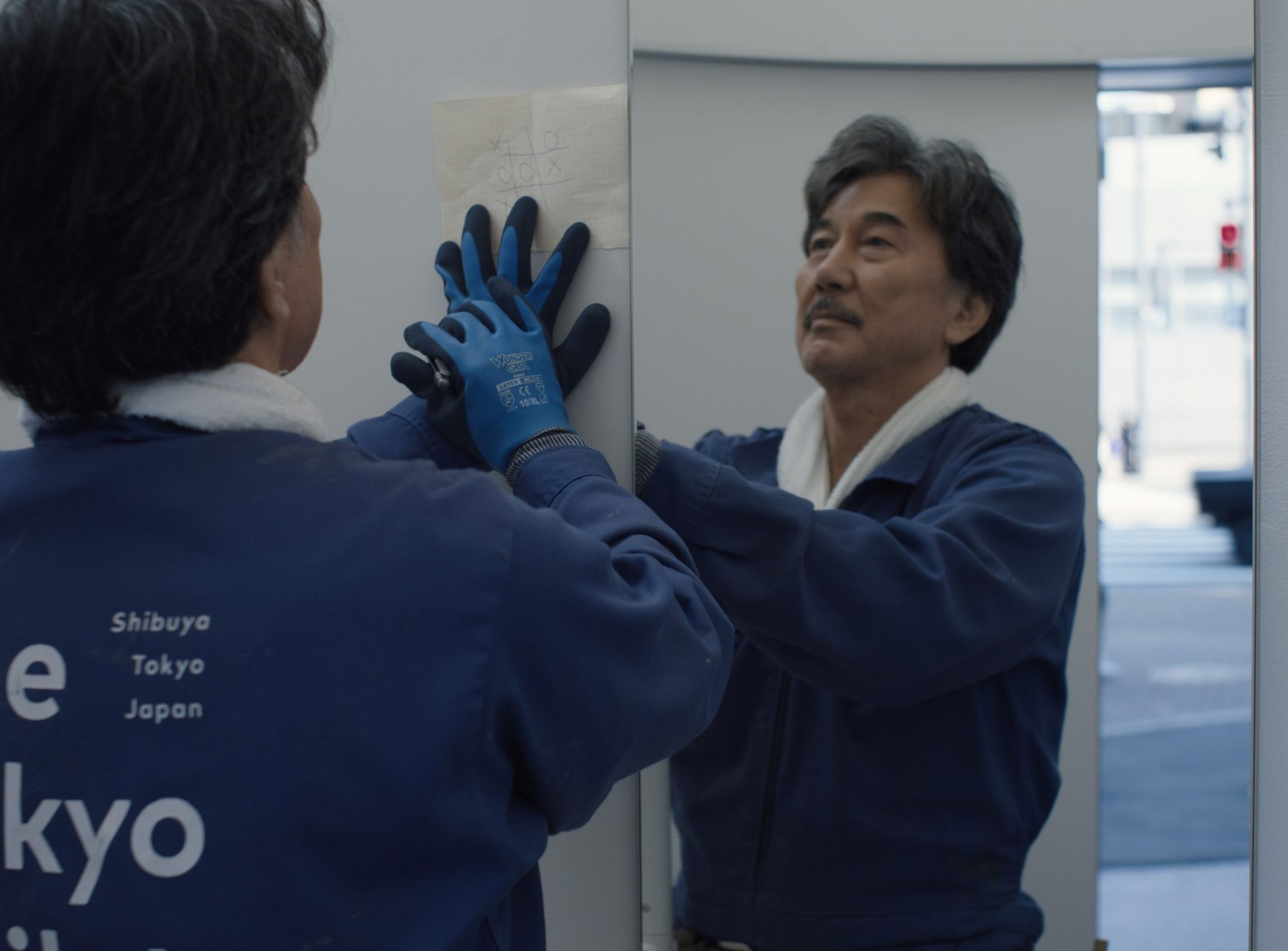

The Tokyo portrayed in Perfect Days is unmistakably the reflection of Tokyo today. Hirayama, played by Koji Yakusho, is a bathroom cleaner who lives in a small residence on the east side of Tokyo with a view of Sky Tree. The area he works in is on the west side of Tokyo, and the public bathrooms he works at are part of The Tokyo Toilet project in Shibuya. On weekdays, Hirayama always wakes up early in the morning without an alarm because someone sweeping outside wakes him up. He brushes his teeth, waters his plants, changes into his cleaner uniform, and leaves the house after fetching his belongings like a watch and some cash. He’s a cash-only person; he doesn’t use QR code payment. He rides a Daihatsu Hijet Cargo, commonly used as a delivery van. It’s a car for laborers. Hirayama goes from the east to the west of Tokyo with a canned coffee for breakfast and music playing from a cassette tape. Here, Wenders illustrates a realistic rhythm of people living on the outskirts of Tokyo, heading from downtown to uptown. This scene, which realistically shows the stark economic differences between the east and west, is handled with perfect balance precisely because Wenders is the master of road movies. The view of the road, lit by the morning sun, will feel familiar to those who know his work. It also appears in Notebook on Cities and Clothes, Wenders’ 1989 film on Yohji Yamamoto.

In pursuit of the image of Tokyo

The days when foreign tourists couldn’t be seen in the city have disappeared. In 2003, there were 5.21 million foreign visitors and 25 million by 2023. The number multiplied by 5 in two decades. After overcoming a period marked by a slump due to the pandemic, the number of monthly visitors entering the country at the end of 2023 surpassed the number in pre-covid 2019. Sightseeing destinations like Kyoto and Niseko are full of tourists from abroad, but Tokyo is the same. There are moments when it feels like over half of the people in Ginza and Omotesando are visiting from abroad. With the help of Japan’s weak yen, the number of people drawn to Tokyo has increased. What sort of idea of Tokyo are the foreign visitors chasing after?

A famous example of a film that successfully visualized Tokyo in the past is Sofia Coppola’s Lost in Translation (2003). The film, which continues to enchant audiences abroad, offers a glimpse of Tokyo culture from an outside perspective. Conflicting cultures, such as technology, karaoke, cosplay, clubs, fetish culture, fashion, music, TV programs, and traditional culture, are mixed and woven within the city. She creates an unidentifiable image of Tokyo that “economic animals” reside in. Figures such as Hiroshi Fujiwara, the late chief editor of DUNE, Fumihiro Hayashi, Kunichi Nomura, who was involved in the location scouting process, and HIROMIX make cameos. The 2003 film captured the hearts of audiences, especially in Europe and America, who were searching for a city where novelty and exoticism coexisted. If you ask the hotel staff, you can actually listen to the tracks that Nigo selected at the Park Hyatt Tokyo, the backdrop for Lost in Translation. Even today, two decades after the film’s release, people visit the city and the Park Hyatt Tokyo to chase after the elusive idea of Tokyo in the film, and they haven’t ceased. I should point out that the film illustrates life in the west side of Tokyo, such as Shibuya and Shinjuku.

On the contrary, in the sense that anyone can access it, the Tokyo depicted in Perfect Days is approachable. It’s not the kind of Tokyo you can’t tap into if you don’t know anyone; it’s not a best-kept secret. It comprises parks, izakaya bars, old bookstores, laundromats, apartments made from wood, bathrooms in west Tokyo, the landscape of a city where its urban development never seems to end, and streets that connect the east to the west. For many Tokyoites, such everyday views aren’t rare, as they’ve encountered them at least once.

A film that was born because it didn’t start out as one

According to the producer and co-screenwriter of Perfect Days, Takuma Takasaki, and co-producer and financer, Koji Yanai, this film was born from various coincidences. The film’s setting, The Tokyo Toilet, is a set of public bathrooms in the Shibuya ward. In terms of toilets, in In Praise of Shadows by Junichiro Tanizaki, he asserts that the mystique and distinct beauty of toilets lie in their gloominess, but what do you, dear reader, think? The Tokyo Toilet is a project in which legendary architects and designers shed light on the shadows of bathrooms. The 17 bathrooms, made by world-renowned architects and designers like Shigeru Ban, Tadao Ando, Nigo, and Mark Newson, were born from Fast Retailing’s Koji Yanai’s curation. Perfect Days

emerged from Koji Yanai and Takuma Takasaki casually brainstorming how to get people to use The Tokyo Toilet bathrooms cleanly. A conversation between Takasaki and Yanai detailing the film’s genesis is in the December 2023 issue, the Perfect Days issue, of SWITCH in Japanese, so I’d recommend you read it*1.

A film made from the opposite end of Hollywood

Wenders is undeniably the master of road movies. The trilogy of Alice in the Cities (1974), Wrong Move (1975), Kings of the Road (1976), and Paris, Texas (1984), a film set in Texas, USA, that cemented his icon status, are all road movies. Perfect Days, going back and forth between the east and the west side of Tokyo is also a road movie. Wenders is also known as a director with a rebellious spirit against Hollywood films*2. One of his inspirations is the films of Yasujiro Ozu, stemming from the opposite end of Hollywood. About the director, Wenders passionately says, “I still think his cinema is truly world cinema…by not being part of the empire of the American census… but by being its own empire.”

When I think about Ozu’s body of work, I’m reminded of a debate between Ryunosuke Akutagawa and Junichiro Tanizaki in Ryunosuke Akutagawa’s Bungeiteki Na Amari Ni Bungeiteki Na (1927). Tanizaki posits that the most crucial factors for a novel are an exciting plot and narrative structure, while Akutagawa argues that there’s also a lot of value in a book that doesn’t have much of a story. Ozu’s films are made from elements that Akutagawa approved of. His works are quiet and have an atmosphere developed from movie sets with meticulous details and beautiful camerawork. There are no bizarre scenes or synopses, but what does exist is this richness born from the continuous changes in the subtle textures. That itself is a work of art. Wenders has been making films with the influence of Ozu, and Perfect Days is a perfect projection of the director’s experience of Japanese cinema.

Ozu’s Hirayama, Wenders and Takasaki’s Hirayama

Takuma Takasaki gave the protagonist of Perfect Days the name Hirayama, which often appears in Ozu’s films, but according to Takasaki, it was a total coincidence*3. In Ozu’s films, the best-known Hirayamas are Shukichi Hirayama (Chishu Ryu), the protagonist in Tokyo Story (1953), and Shuhei Hirayama (Chishu Ryu) in An Autumn Afternoon (1962). The everyday lives of the Hirayamas in Ozu’s films seem like they were the norm for Japanese people at the time, but that wasn’t the case. Japan was still poor in the 60s. Akira Kurosawa’s Dodes’ka-den (1970) was made after An Autumn Afternoon, but it’s set in a poor and rough city. Nagisa Oshima’s Night and Fog in Japan (1959) was created in the 50s, like Tokyo Story, but again, the setting is a rough Tokyo, and the protagonist is a poor child. Even though these films existed in the same Showa era, the worlds Ozu built were rich.

In Tokyo Story, among Hirayama’s children are a private physician and a teacher, respectively, and in An Autumn Afternoon, the protagonist Hirayama holds an important role at a corporation in the Marunouchi area, and many of the characters are white-collar workers*4.

*1 An interview with the people involved in the making of Perfect Days is on the official account of Bitters End, the distribution company for the film. It’s interesting to watch it paired with the film.

*2 Hollywood films are known for gun fights, war, heroic tales, love stories, the bottom pit of capitalism, and the American Dream. Many of them have scenes that could actually happen in American society. It can be said that the reality of American culture has given Hollywood films a sense of reality, but it can’t be said the same films seem realistic in other countries.

*3 This anecdote is mentioned in a short interview with the co-screenwriter and producer of Perfect Days, Takuma Takasaki, in POSTGENDAI, an online magazine.

https://postgendai.com/blogs/postgendai_dictionary/takuma_takasaki

*4 In An Autumn Afternoon, the marriage arrangement of Hirayama’s daughter, Michiko Hirayama (Shima Iwashita), comes up, and one can tell that Hirayama leads an affluent life from the fashion in the film. Hanae Mori designed the costumes for Shima Iwashita. Hirayama’s furniture and the Japanese restaurant in the film all look like they could be in Katei Gaho.

In Perfect Days, in a scene where Hirayama’s sister appears in a Lexus with a personal driver, we discover that Hirayama comes from a wealthy family but left them of his own volition and lives quietly on the east side of Tokyo. It made me wonder if Hirayama from Perfect Days could be a relative of the Hirayamas from Ozu’s films.

In Anna Karenina, Tolstoy opens with, “Happy families are all alike; every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.” Many films made in the same period as Ozu’s are set in a world rife with social issues. Perhaps Ozu, who was drafted into the military in World War II and led a turbulent life, chose happy worlds of their own kind as the settings of his films because he felt his aesthetic could stand out precisely because the settings are alike.

Hirayama from Perfect Days was given the role of cleaning bathrooms. Unlike the one in Ozu’s and Kurosawa’s era, the Tokyo he lives in is one after Japan’s rapid economic growth. Tokyo, which overcame the “lost 20 years” after the economic bubble burst, isn’t a place where Hollywood-esque stories could shine. Through Hirayama’s life, we’re reminded of the richness of everyday life in Tokyo, which we’re prone to forget. Watching him spritz water on his plants, taking photos of komorebi (sunlight through the trees)*5, falling asleep while reading, and dreaming, I can see that he understands the fulfillment of such a life. It makes me want to agree with him quietly*6.

Opposing the gaze of Orientalism

In 2023, Japan ranked first worldwide on the Nation Brands Index (NBI) for the first time*7. I believe rankings have little meaning, but I didn’t expect Japan to be number one worldwide in the same year a prominent film from Japan was released.

Perfect Days is captivating audiences across the globe, not just in Japan. At the Cannes Film Festival last year, Koji Yakusho, who plays Hirayama, won Best Actor, and the film was nominated for the Academy Award for Best International Feature Film this year. In January, it was number one at the box office in Italy, and the other day, an event held at the Chinese Theater the night before the American release was a success.

Other countries will inevitably view Japanese films made with an international audience in mind through an Orientalist gaze. What they seek is the essence of the East. Many films have managed to meet such expectations. Akira Kurosawa, mentioned above, and Takeshi Kitano, who makes films about human relationships in the underbelly of society, could be examples. The same could be said about films that extracted social issues that became topical in Japan and illustrated them in a way foreign audiences can understand. The same gaze is probably on Perfect Days, but the Tokyo that Wenders, a foreign director, captured manages to neutralize such extreme expectations.

The notion that imported things are supreme is ingrained in Japanese people. This is to be expected because people have been borderline overdosing on music, literature, and fashion from the West, and especially American culture. As a result, aside from the reverse import of Japanese content, a strange phenomenon in which Japanese people, living on the opposite end of Western society, don’t appreciate Japanese content tends to occur*8. It becomes clear that Hirayama is also strongly influenced by Western culture, as he prefers American music and novels. The production team, like Takuma Takasaki and Koji Yanai, is probably the same. They met Wenders, someone who has been following Japanese films for around five decades, and portrayed the contemporary image of Tokyo; that’s one significant story in itself.

Perfect Days’ idea of Tokyo has given new meaning to Tokyo. The landscape of Tokyo that we know was spread to the world; one of the film’s successes lies in how we can talk about it regardless of where we’re from. The last scene where Nina Simone‘s ‘Feeling Good’ plays is inside Hirayama’s van as he drives it. The inside of a car is a small space that can exist anywhere in the world, not just in Tokyo. The scene stirs something within us; our own memories of life flicker in our minds. Much like Hirayama feeling the sound of the car engine in the driver’s seat as he goes from east to west of Tokyo, we, too, feel the hum of contemporary Tokyo in our seats in the movie theater.

*5 Donata Wenders took some of the images of the komorebi in the film, which were exhibited at 104 Gallery from December 22nd, 2023, to January 20th, 2024, under the title KOMOREBI DREAMS: supported by THE TOKYO TOILET Art Project/MASTERMIND.

*6 In an essay in Murakami Asahido, Haruki Murakami uses the term “simple pleasure” to mean small but certain happiness. This can also be applied to Hirayama’s daily life. It signifies the fulfilling feeling of mundane yet certain pleasures in everyday life, such as drinking a cold beer after working out.

*7 Anholt-GfK Nation Brands Index uses six criteria to evaluate certain countries: culture, people, tourism, exports, governance, and immigration and investment. Japan was ranked first for the first time in 2023.

You can look at the past rankings on Wikipedia. Until Trump got elected in 2016, the US was almost always at the top.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nation_branding

*8 The dancing of Min Tanaka, who appears as a houseless person in the film, can be seen in Somebody Comes into the Light (music by Jun Miyake), a short film. Speaking on dancing, he touches on Ame-no-Uzume’s dancing, which appears in the Kojiki. Today, dance in the West is predominantly founded on ballet. Initially, different dances existed everywhere among indigenous groups, but they became extinct because of colonialism and the changing times. He mentioned that thinking within a Western framework can be limiting if we were to return to the idea of dance. It speaks to Wenders’ ideas regarding Hollywood films.

Director: Wim Wenders

Screenwriter: Wim Wenders, Takuma Takasaki

Producer: Koji Yanai

Cast: Koji Yakusho, Tokio Emoto, Arisa Nakano, Aoi Yamada, Yumi Aso, Sayuri Ishikawa, Min Tanaka, Tomokazu Miura

Production: MASTER MIND

Distribution: Bitters End

2023/Japan/In color/DCP/5. 1ch/Standard/124 minutes

© 2023 MASTER MIND Ltd.

Website: perfectdays-movie.jp

Translation Lena Grace Suda