Families are sometimes messy and unconventional; they’re unique, and it’s hard to put them all in the same box. Berlin-based artist Rie Yamada tells the story of such a family, separated into three different works: past, present, and future. In her first work Familie werden (in German, become a family), published in 2017, Rie single-handedly acts as different members of ten Japanese and German families; with this project, she was awarded the “gute aussichten: new german photography” award. She created her second project, Familie suchen (in German, search for a family), based on her own experience with Japanese marriage matchmaking services. This project was set up as an interactive installation making use of a mirror and self-portraits of Rie dressed up as the 63 men she met during the matchmaking events, with the goal of asking ourselves what our true self actually is. “I’ve lived my life turning my eyes away from the concept of family, without intervening too much. I’m creating art to settle things with this concept I’ve turned a blind eye to,” reveals Rie, while we talk about her vision of family, her present and future art projects and more.

Days of exhaustive research and practice

–Can you tell us the reasons behind your new project Familie suchen?

Rie: I’m over the marriageable age, and I didn’t even really want to start a family; I’m not married. When you consider or try starting a family, one of the keywords is “marriage.” I started my research focusing on Japan, where searching for a partner specifically for marriage (marriage hunting) is widespread; I’m concerned about the values and behaviors of modern people’s families, as well as the reasons for building one.

–You’ve been actively participating in Japanese speed dating parties for your research; how do you prepare before going to such events?

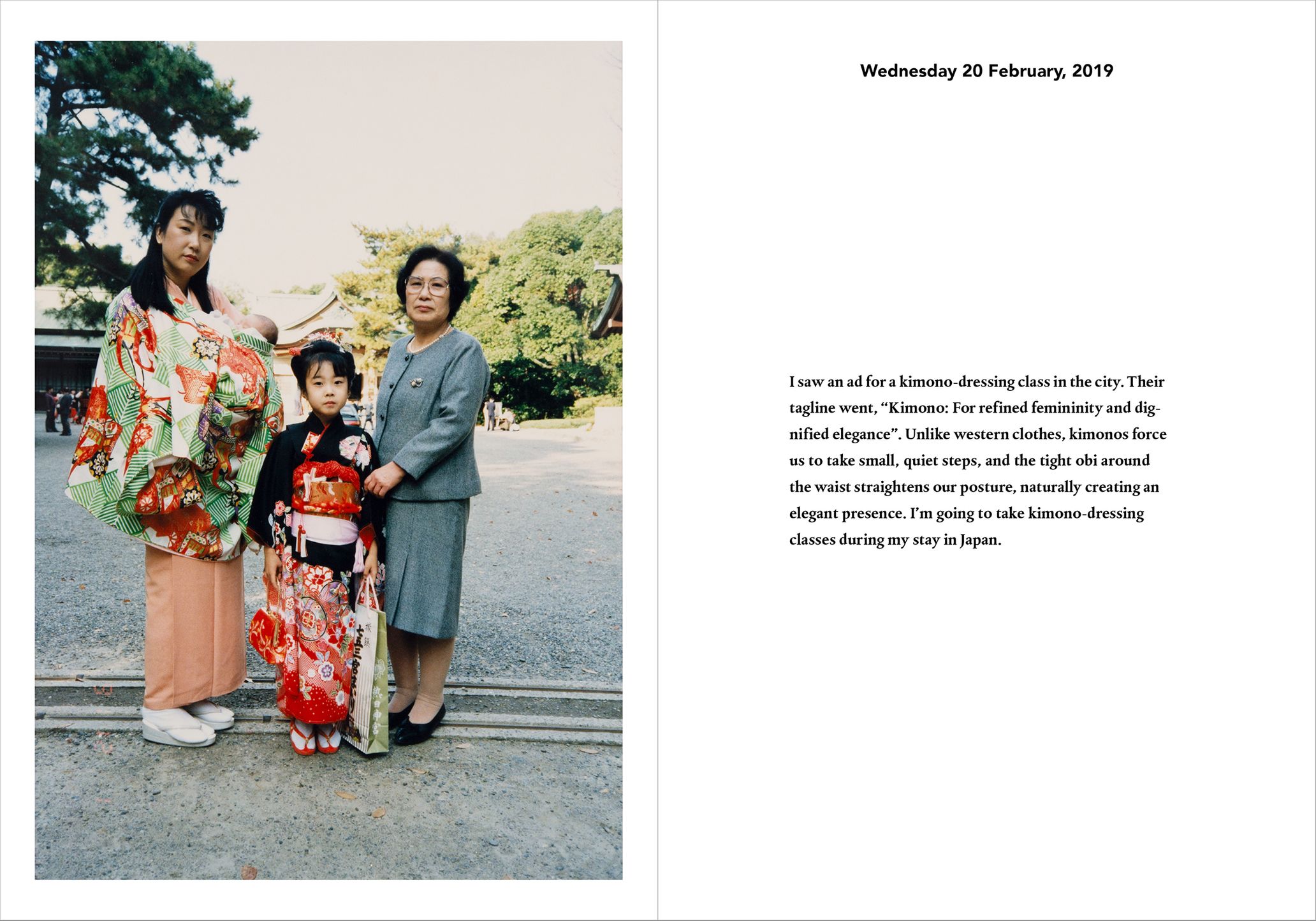

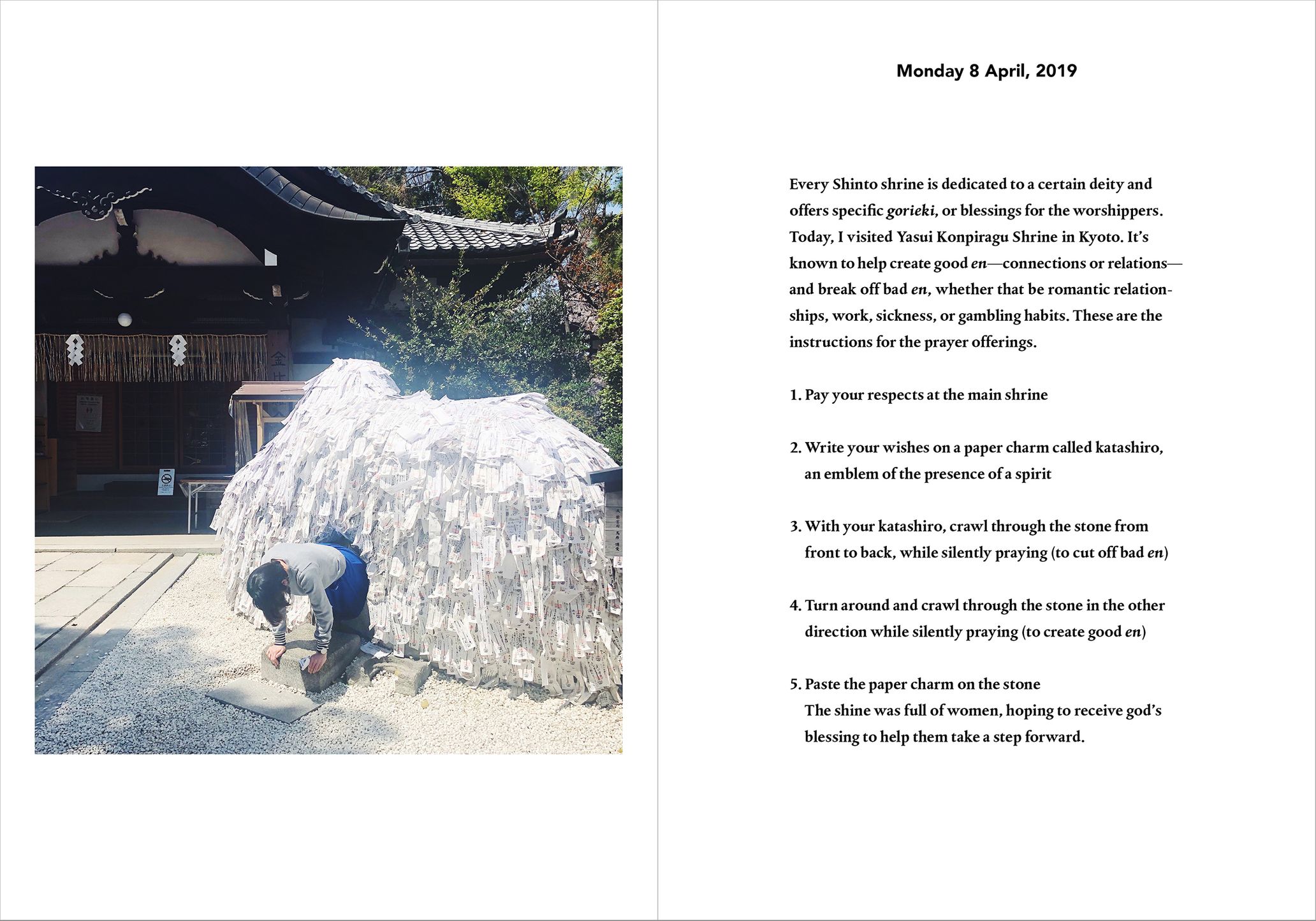

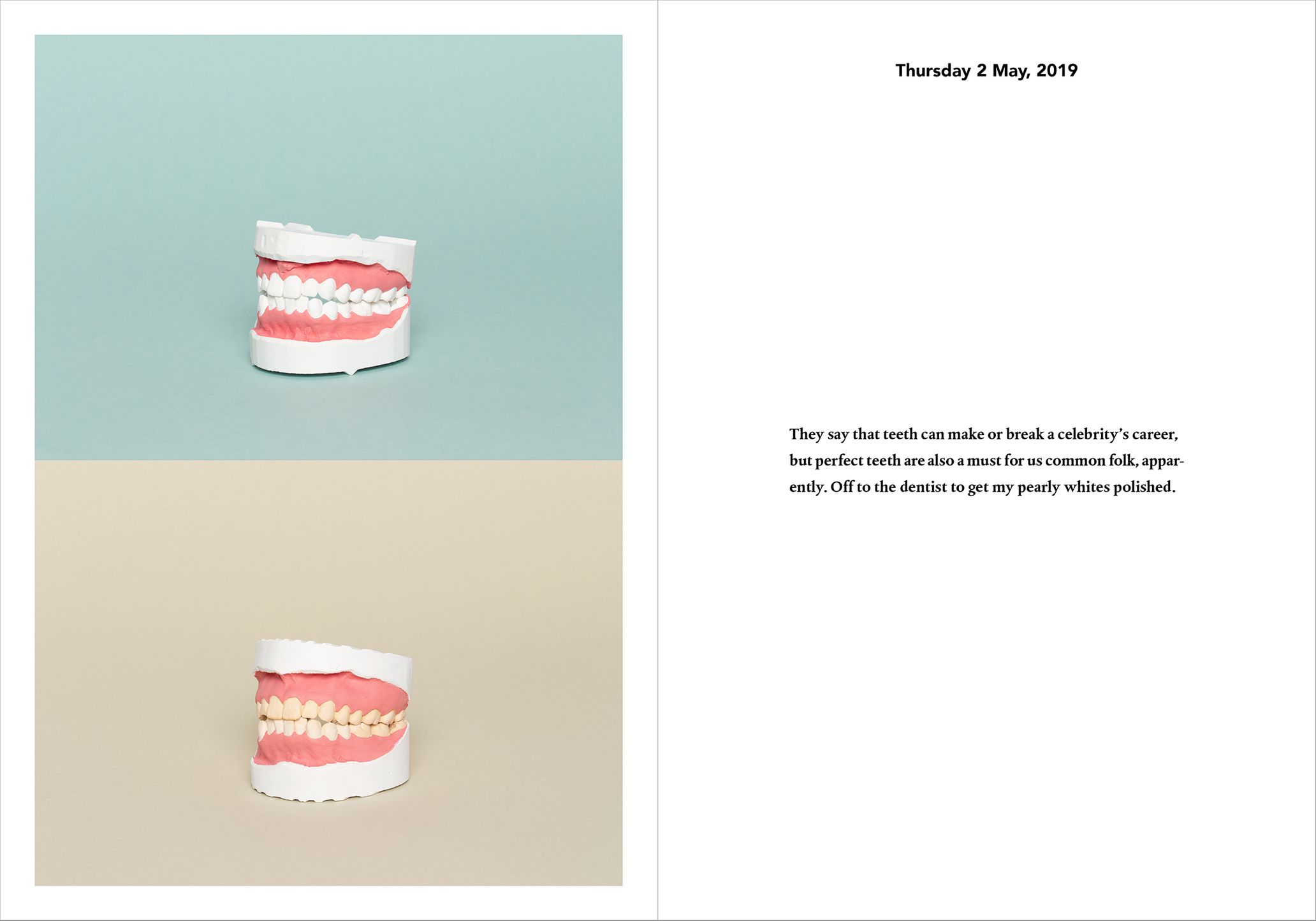

Rie: To gain a general sense of how it works, I researched what women focus on for marriage hunting and put it into practice. First of all, I joined a gym on New Year’s Day 2019; I thought that if I didn’t do it on the first of the year, I would end up never doing it (laughs). I learned how to put on a kimono just to able to write it on the special skills section of my profile card. I also whitened my teeth, put on contact lenses, went to a hair salon and changed my hairstyle to something more soft and fluffy; I even had my fortune told with tarot cards and prayed to the god of Izumo Taisha, a sacred shrine famous for being the home of the deity of marriage. I went to class reunions and blind-date izakayas; I basically practiced what everyone does for about a year. I summarized my research activities in an installation booklet as a “marriage hunting diary.”

–I guess your lifestyle completely changes, right?

Rie: It made me realize how many things I was procrastinating on. I thought it was fine for me, but I noticed that, for society, it’s not. I don’t think it’s normal, but I was ok not doing them. The only things I kept doing after I was done with the project are going to the gym, care about my teeth and putting on contacts. I also wanted to learn more about Japanese culture, so learning how to properly wear a kimono was kind of two birds with one stone.

Discovering your “true self” through marriage hunting parties

–So, after such preparations, you decided to attend marriage hunting parties.

Rie: In 2019, I stayed in Japan for one month and returned to Germany four times. I wanted to meet as many different people as I could in short periods, so I mainly attended those events on weekends when there are more people; I’d even go to two or three parties in a day. This is apparently pretty normal, so you often meet the same participants from the previous parties. I went to more than 50 parties in four different locations: my hometown of Nagoya, Kantō, Kansai, and Kyūshū; I met people that varied in age, from guys in their early twenties to mid-fifties. I’d also choose the events based on what the participants would comment on them.

–Are there any people who left an impression on you?

Rie: A man in his thirties wearing a suit; he was in his second year of marriage hunting. He was stuck in a loop, tired of it, and he advised me to decide on someone in my first three months: if you meet too many people, it gets hard to make a decision, and you may end up not even knowing what kind of person you want to meet. That being the case, he couldn’t decide on a partner, but he still had nothing to do on the weekends, so he continued to go to these parties. Another one who left a strong impression on me was a woman who’d often socialize with the other female participants. She told me that befriending other women at these events improves your chances of finding a partner because they would often invite you to gokon parties or introduce their guy friends to you. She was clearly someone who was deep in the marriage hunting game. The most memorable profile was the one of a vice chief priest of a Buddhist temple in his thirties; he loved his scooter.

–Meeting a lot of people in a short amount of time expanded your understanding of your project and your questions about it. At that time, did you notice any changes in yourself?

Rie: My communication skills improved, as well as my ability to observe others and myself. At first, I saw my activities as a project, but as I kept at it, I started worrying about what kind of woman people want to marry and what to change about myself to better fit that mold. I gradually felt myself falling into an identity crisis, and I began to think about myself, as seen from the other person’s perspective, and my “true self.”

–What do you mean by “true self?”

Rie: I was concerned about how the other person would see and judge me, so I would put away my personality and image of myself; I’d control and limit my feelings, and my “fake self” would come out. I fell into the illusion of losing my ”true self,” although I did know there is no answer to what my “true self” is: your self-image is affected by the influence of others and your own belief, your freedom, and other people’s approval. That’s your “true self,” which we find by being accepted by others, be it in marriage hunting or society. I put too many restrictions on myself and my emotions, and I looked at myself through other people’s eyes, facial expressions and reactions too much, like staring at a mirror. However, thanks to that, I was able to once again reflect on the significance of using “family” as a theme for my art and the value of my own existence.

An installation with a mirror as a metaphor

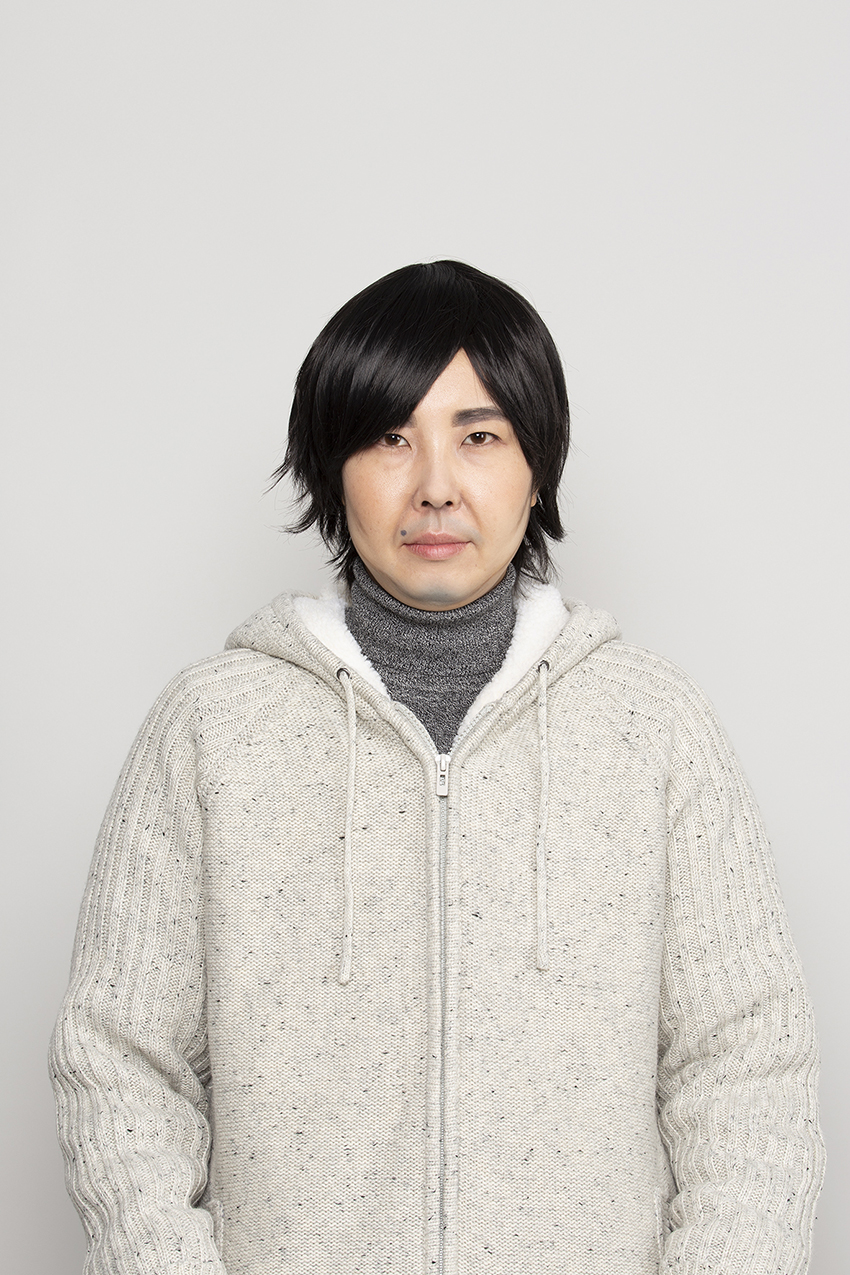

–For your project, you acted and dressed up as the 63 men you met through such marriage hunting events; did you do everything by yourself?

Rie: Yes, I did everything in Berlin, based on the sketches and memos I drew from my memory. I bought the clothes at second-hand clothing stores or borrowed them from some friends, and I already owned about 60 wigs, but I had to buy more. At the university studio, I was taking pictures of myself dressed up like three, four different people a day. Sometimes some students I didn’t know would come in and be startled by what I was doing. I could’ve used Photoshop to process the faces I was trying to re-emulate so they would look closer to the original person, but I had the confidence that I could do that only with make-up and facial expression, so I didn’t retouch them. I prepared a full-length mirror next to the camera and took the pictures with a self-timer.

—Familie suchen seems to be an installation rather than an exhibition.

Rie: I built it as an interactive installation to get closer to my experience. The participant starts by seeing themself in the mirror, which is actually a magic mirror. When they sit down, a built-in sensor reacts, and the tablet on the desk boots up. As they scroll like in a matching app, the mirror becomes a monitor, and it shows a portrait of the man the participant selected. When you try to look at yourself in the mirror, you see yourself through the other person’s eyes. The mirror is a metaphor; I’m adopting it as my point of output. VIVITA provided their prototyping tool VIVIWARE Cell, and their engineer Fumio Yamamori helped develop the control program.

–How was the reaction overseas?

Rie: I had the installation open to the public once in the middle of production, but after that, it became impossible due to the pandemic. Although online-only, I presented it as my university graduation project. First of all, it was hard for people to understand the concept of marriage hunting. In Germany, they have speed dating, but it’s not for marriage purposes, so even if they can understand what marriage matchmaking services are, they may not be convinced of the reason why people would do that; they would experience some sort of culture shock. On the other hand, many people would connect the dots and recognize the mirror as a metaphor. This year’s exhibition will be outside of school, so I’m looking forward to seeing what kind of feedback I’ll receive.

–Are there any other differences between Japanese marriage hunting and German speed dating?

Rie: In Japan, the main premise is to find a marriage partner, but in Germany, it’s not the same: in Berlin, there are speed dating services such as Fisch sucht Fahrrad (in German, fish seeks bike) and Topf sucht Deckel (in German, pot seeks lid), which start in clubs on weekend nights. They’re different from Japanese group matchmaking services. I couldn’t research in Germany due to the pandemic, but I hope to be able for my next project.

A personal, unconventional family

–Are there any differences in the way Germany and Japan see marriage and family?

Rie: Even though the household legal system(Ie seido) was abolished after the war in Japan, many people have particular feelings toward marriage and family because of the family register system(Koseki) and the concept of “household,” deeply rooted in the mind of Japanese people. In Germany, the system is managed on an individual basis rather than a household one. the system is managed on an individual basis rather than a household one. You can discuss and decide with your partner whether you choose to get married or not, so society recognizes a diverse range of moral values on the matter.

–Has your personal view of marriage and family changed with your projects?

Rie:When I was working on my previous project Familie werden, I didn’t want to get married, but now I don’t care whether or not I do. Living in Germany made me realize that it doesn’t really matter whether you’re married or not. Also, through my projects, I came to understand that our roles within a family are not defined. Here in Germany, I’ve met many people who live their life unapologetically, regardless of age or gender. I’ve come to realize that you can take on several roles, even if you’re just one person.

–If there is no fixed division of roles, there is more than one shape of family.

Rie: Soon enough, families of one will be considered families too. In Japan, if you don’t marry, you’re seen as a loser, and if you do, you’re seen as a proper adult; to this day, I’m still questioning this trend of society. The concept of family always matches its era, and it transforms to conform to it. We are now in an era where we can choose for ourselves. In the 21st century, we can pursue the shape of family that suits us. Now that social changes have diversified our activities, interests, and time spent outside the family, the need to belong to a family is less prominent. Now that households and families are no longer the predominant social units, they will be replaced by individuals.

–It’s an unconventional, new shape of family. This year, I hear that you will finally start producing the third part of your project.

Rie: That’s right. For the third part, Familie gründen (in German, start a family), I’m planning to include both Japan and Germany again in the project. The theme is about what kind of family I will build and how.

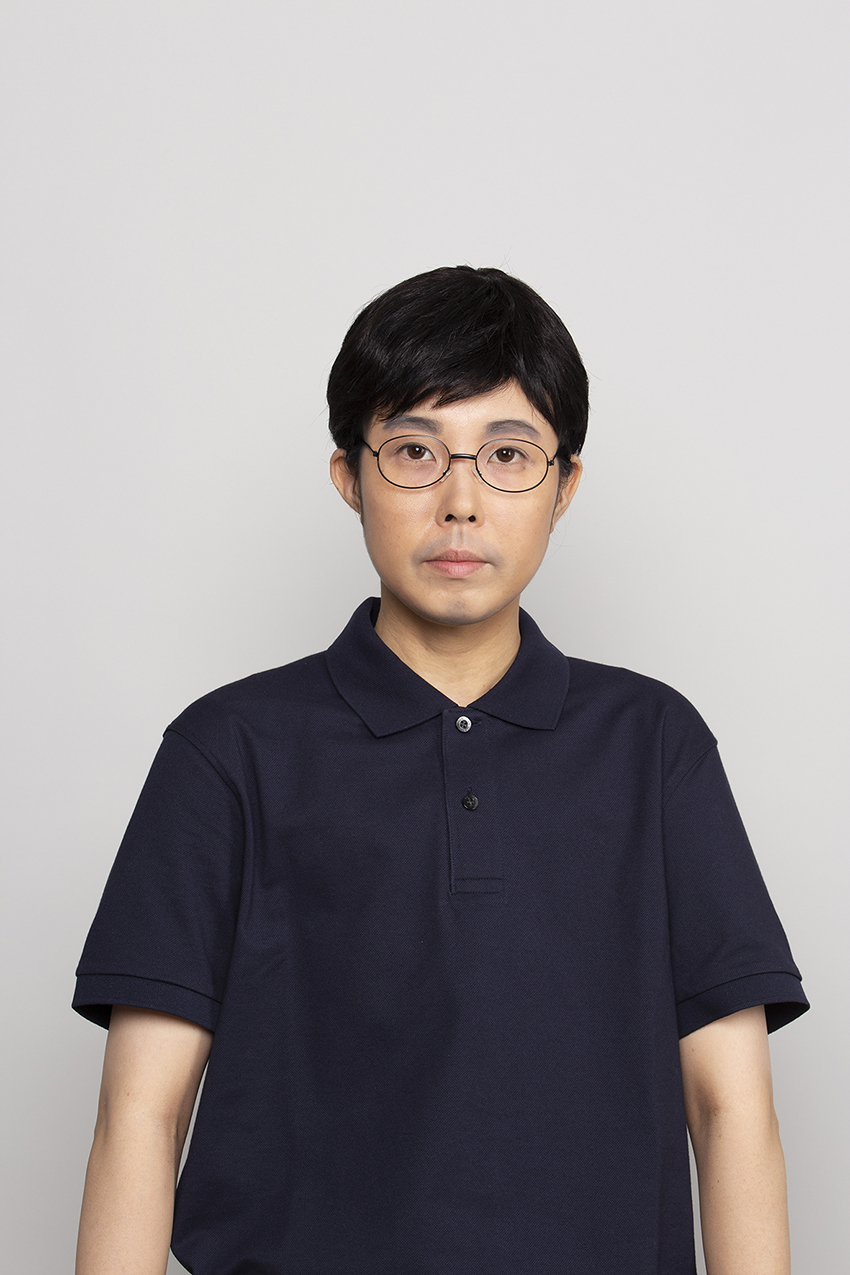

Rie Yamada

Born in Aichi prefecture, Rie Yamada is an artist based in Berlin. She moved to Germany in 2011 and enrolled in the Weißensee University of Fine Arts in Berlin. She won numerous awards, including the “gute aussichten: new german photography” award for her project Familie werden. She completed her master’s in 2020 and is currently enrolled in the Meisterschüler program. She will be holding a solo exhibition in Cologne in 2021 and Novi Sad in 2022. She also produces art pieces in the fields of fashion and culture.

www.rieyamada.com Instagram:@rie_bergfeld

Picture Provided: Rie Yamada

Translation Leandro Di Rosa